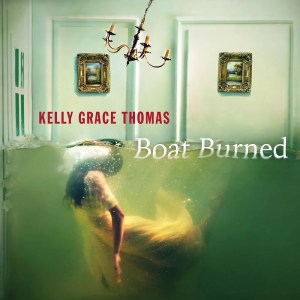

YesYes Books. 2020. 110 pages.

YesYes Books. 2020. 110 pages.

Reviewed by Heather Myers

Kelly Grace Thomas, in her first full-length poetry collection, Boat Burned, writes, “She told me: pain needs a witness.” This line from “Storm Warning” lingered with me long after I finished the collection. After all, why do we write what hurts? Apart from personal trauma and pain, the collection looks expansively at racism, America, and the societal expectations imposed upon women. There is also love and tenderness to be found within this work. Boats, and the seas upon which they ride, shimmer and burn throughout the collection, taking on different meaning and tone such that the metaphors never become dull or overdone.

Thomas discusses Boat Burned in an interview with Hannah Lazar in The Penn Review, stating that “The Boat of My Body” came to her when she wondered, “’What if every woman took off her clothes and there was something that wasn’t human underneath?’ and then I thought ‘I’d be a boat.’” The idea of defamiliarizing the body, or the body taking the shape of something else more expansive, is a significant thread throughout the collection—revealing, I think, of the ways the speaker balances the tension of seeking comfort and familiarity within the body while also reconciling with its strangeness and discomfort. The body, then, is written malleable and vessel-like, heightening awareness of how we are to perceive our own conceptions of image and what constitutes beauty. In “The Polite Bird of Story,” Thomas turns inward to the rooms that make her, and what they house—the interior life is very much constructed by the familial. The poem acknowledges that this is part of how the body is formed—through another’s shaping and rearing. Thomas’s skill for writing intimately into the self shines here:

Take flight, against God or the sky.

We are always open domes looking for rest.

The linoleum stung with spill.

The cabinets full of hard parts.

I have been thinking about the shells

of Russian Dolls snapping like twigs.

This moment echoes an earlier moment in the collection, from the poem, “We Know Monsters By Their Teeth,” “The small death of letting / go. Rest a four-letter word.” Incidentally, monsters are also mentioned in “The Polite Bird of Story” (and in other moments throughout the collection). The lines, “Sometimes there is too much female—they call it monster. I roil a tiny teakettle behind these picket teeth. Perfection” examine anger at society, and how femininity constructs the speaker. All of these portraits within the poem culminate in the final lines, “Food is just another ghost story / the starved like to tell.” The examination of eating disorder is integral to the collection, and to femininity and body image within this work—how to inhabit the body, especially when it is a ‘vessel’ we do not want to be contained within.

Womanhood presents and nesting-dolls itself into the speaker through generations of women before her. The women in these poems often show and tell the speaker how to think and behave, particularly when the speaker regards her body. I was most drawn to the moments when the body is defamiliarized or becomes something else entirely. The poem in the form of a word problem, “In An Attempt To Solve for X: Femininity as Word Problem” grapples head-on with the central conflict of the collection: the ways in which women deal with shame. The opening lines in this poem examine femininity’s ties to shame and highlight the difficulty in addressing the body, especially considering the way society shames women about having sex and eating food. Thomas writes, “Possible answers: Don’t say / the word body. Or become / a slow crawl of thigh highs.” Through the form of a word problem, the poem breaks down and subverts constructions of learned shame that come with being a woman. What is at the center, it seems, is the speaker’s recovery for the self. Becoming, the collection highlights, is an unending process.

Word problem as map: You

are the smallest place you know.

Possible steps to solving for y (you)

1) Give back the rib 2) Eat every apple

until you are fat with orchards 3) Dress

in snake and dig a grave.

A map, after all, is necessary for navigating both the sea and the self.

In the poem, “I’ll Never Return,” Thomas discusses the body as a place of longing for home. The lines, “My skin is a map of looking back. I swallow every place / I cannot keep. Always / fear I’ll never return” point to the body also as a place of memory. In this particular poem, Thomas’s husband, Omid, is in scene with the speaker, in a recollection that “Omid tells me/ I hold my breath.” Omid’s presence in the collection allows the work’s dialogue to expand and look more at America and its obsession with image, particularly the racism Omid, who is Persian, experiences. The poems about Omid’s beard, for example, show Thomas considering another’s body and America’s foreboding presence in the collection.

Boat Burned starts with “Vesseled,” foregrounding burning, in the first stanza:

Here’s how it happened: I burned each boat

But first they flamed

Me. I knew what I was

A vessel he could float

And then the final stanza of the poem:

The ocean, my witness,

watches the body cross

itself. I hold a match

to everything I no longer am.

Thomas’s powerful crafting is evident in her attention to enjambment: in each line, it feels the speaker is arriving anew: “Me. I knew what I was”—all the way through to the final two lines, “itself. I hold a match / to everything I no longer am.” This renewal, akin to rising from the ashes, is an idea echoed in the collection’s closing poem, “Boat / Body.” The poem, ultimately, is a triumph of self-discovery: “…I will not kneel / for a man’s affection. Women, keep / this world bloomdizzy.” Thomas calls the reader to partake in this arrival along with the speaker:

Teach these teeth

to tender. We are swollen

with tomorrow. It’s time to holy

one another instead. Salt water

saints. Crowned in sea foam.

The blue of each majesty.

They can’t sink us

If we name ourselves

sea.

Today, here forward, I will think of myself as sea.

Heather Myers is from Altoona, PA. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from West Virginia University. Currently, she is a third year PhD student and instructor at the University of North Texas. She is the recipient of a 2018 AWP Intros award, and her poems have been published in The Journal, Palette Poetry, Puerto Del Sol and elsewhere.